Ayuel Kacgor (27), from Sudan, is an MSc student studying Aerospace Engineering. He hasn’t been back to his war-torn country since arriving here in Delft five years ago.

No one knows exactly how many people have died in the violence raging in Sudan since early 2003, but estimates range from 60,000 to 400,000 victims. Kacgor believes a scientific approach can help solve the political instability in Sudan.

Ayuel Kacgor opened the door a few seconds after I rang the bell, warmly inviting me into his home and introducing me to his Sudanese friend, Dedi, a huge man with a powerful handshake. While Kacgor prepared for the interview, I cheerfully conversed with Dedi, who explained that he’d been granted asylum in the Netherlands. Dedi said he used to work in the security industry in Sudan, but that it wasn’t safe there anymore. I asked if danger wasn’t inherent to his profession. His smile faded. “Nobody is safe in Sudan,” Dedi replied.

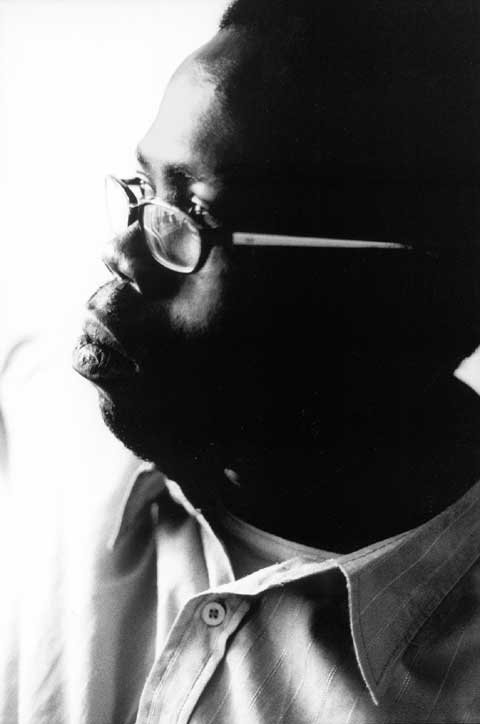

Kacgor, smaller of stature, reappeared with coffee. He had showered and changed clothes, wore sandals on his feet and steel-rimmed glasses adorned his bright face – a thinker. Kacgor spoke of exclusion, identity, the situation in Sudan and the future of Africa.

What are the roots of the tragedy unfolding in Sudan today?

“Civil war has engulfed my country since its independence from the British in 1956. The southerners opposed the fact that they were excluded from the independence process. This continued until 1972, when the government signed a peace treaty with the southerners. In 1983, the government reneged on the peace agreement, war broke out again, and the Sudan Peoples Liberation Movement (SPLM) was founded with the aim of supporting every Sudanese person who feels excluded from the system.”

So it’s not just the southerners who are being excluded?

“There are many people who are excluded from Sudan’s political system. The Sudanese government’s consistent policy has been to marginalize and exclude people from the south, Darfur, Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, eastern Sudan, and far north. The centre, and only the centre, is Sudan for the governing body. They see the capital Khartoum as Sudan. All development and investment is focused there.”

This governing body is dominated by Arabs, right?

“Sudan’s government is dominated by a small clique of Islamics. The current civil war is between southerners, opposing the system, and the government, who are trying to maintain it. It’s not a war based on ethnicity or religion; it’s a war being fought against injustice and exclusiveness.”

What kind of government do you want to see in power?

“Democratic – it offers everybody a chance to contribute and be part of the system. If everyone’s represented in government, no one fights the government. The current Sudanese government knows, though, that they wouldn’t rule a democratic Sudan, because African indigenous people are the majority. So the government excludes the majority and makes sure they have less access to education, development and opportunities in general.”

How do you view the current situation in Sudan?

“I study control and simulation at TU Delft. I try to devise mathematical models to describe systems. When you make a model, you must create stability in the model and ensure the process controller is stable. Stability is key. The ‘government system’ in Khartoum says that Sudan is an Islamic, Arabic country; they’ve forced the Arabic language on the Sudanese people, yet 70 percent of Sudanese don’t speak proper Arabic and there are many religions practiced, not only Islam. So it’s not only these two parameters that define Sudan; there are other parameters that define us. You must include all the parameters, including Arabs and Islamics.”

Do you think science can solve Sudan’s political problems?

“Mathematics is the most credible tool to describe nature. I believe it can be used as a tool to come up with solutions for political problems. When you come to Sudan or Africa and want to start making definitions, start making a system, you must include all the parameters. This is a very basic factor. It’s essential that everyone be represented inside their own country and government.”

Is it not possible to have both stability as well as an Islamic government in Sudan?

“It’s an issue of identity. We define ourselves as Africans, they as Arabs. You cannot and should not force an identity upon anyone. Someone owns an identity, so if I want to join an identity, the people that own it should accept me. There must be willingness from both sides, but the group of people owning an identity has the authority to accept you or not. For example, I can only call myself Dutch if the Dutch accept me as such.”

What then is important for establishing peaceful coexistence?

“You don’t need to force people to learn your language, to join your religion; you shouldn’t force them to join your identity. You can let people be as they are and see the common things that you share, focus on those things, and join people on those grounds.”

You’ve lived in the Netherlands for five years. Do you see a future for yourself here?

“Holland is nice; it’s safe here. There are tremendous opportunities for a good education here. TU Delft’s known around the world. If I’m lucky I’ll work in the aerospace sector, but right now I’m focused on my studies. I’m looking forward to my internship in Zurich in July. Of course I’d like to work in Sudan in future, but I’ll cross that bridge when I get there.”

What is your identity?

“I see myself more as an African than as Sudanese. If other African countries are struggling in instability, I cannot live well in a stable Sudan. When I speak to other African students, we all agree that it’s important to look out for each other’s interests.”

Is there such a thing as an African identity?

“Yes. For example, even though there’s huge tragedy taking place in Darfur, the African Union’s helping to solve it. Sudanese and Ugandan troops will also soon be deployed to keep peace in Somalia. These are good examples of sharing resources between African nations. This is a great step towards real unification.”

What are some positive developments in Africa today?

“Corrupt governments, dictators, are slowly being forced out of the African Union, paving the way for democracy. The president of Togo was recently forced to step down because he wasn’t democratically elected, for example. This is a very positive development for all of Africa. Hopefully in future all Africans will realize that we share a lot of traditional values and customs.”

I left Kacgor’s home that day wondering what parameters define me, what my identity was and whether it was an identity that could be owned by people of different nationalities, religions, sexes, races…an identity that always seeks the common ground, no matter how big the differences. I liked to think so, and I hoped I wasn’t the only one.

Ayuel Kacgor (Photo: Hidde van der Lijn, BSc, Netherlands)

Ayuel Kacgor opened the door a few seconds after I rang the bell, warmly inviting me into his home and introducing me to his Sudanese friend, Dedi, a huge man with a powerful handshake. While Kacgor prepared for the interview, I cheerfully conversed with Dedi, who explained that he’d been granted asylum in the Netherlands. Dedi said he used to work in the security industry in Sudan, but that it wasn’t safe there anymore. I asked if danger wasn’t inherent to his profession. His smile faded. “Nobody is safe in Sudan,” Dedi replied.

Kacgor, smaller of stature, reappeared with coffee. He had showered and changed clothes, wore sandals on his feet and steel-rimmed glasses adorned his bright face – a thinker. Kacgor spoke of exclusion, identity, the situation in Sudan and the future of Africa.

What are the roots of the tragedy unfolding in Sudan today?

“Civil war has engulfed my country since its independence from the British in 1956. The southerners opposed the fact that they were excluded from the independence process. This continued until 1972, when the government signed a peace treaty with the southerners. In 1983, the government reneged on the peace agreement, war broke out again, and the Sudan Peoples Liberation Movement (SPLM) was founded with the aim of supporting every Sudanese person who feels excluded from the system.”

So it’s not just the southerners who are being excluded?

“There are many people who are excluded from Sudan’s political system. The Sudanese government’s consistent policy has been to marginalize and exclude people from the south, Darfur, Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, eastern Sudan, and far north. The centre, and only the centre, is Sudan for the governing body. They see the capital Khartoum as Sudan. All development and investment is focused there.”

This governing body is dominated by Arabs, right?

“Sudan’s government is dominated by a small clique of Islamics. The current civil war is between southerners, opposing the system, and the government, who are trying to maintain it. It’s not a war based on ethnicity or religion; it’s a war being fought against injustice and exclusiveness.”

What kind of government do you want to see in power?

“Democratic – it offers everybody a chance to contribute and be part of the system. If everyone’s represented in government, no one fights the government. The current Sudanese government knows, though, that they wouldn’t rule a democratic Sudan, because African indigenous people are the majority. So the government excludes the majority and makes sure they have less access to education, development and opportunities in general.”

How do you view the current situation in Sudan?

“I study control and simulation at TU Delft. I try to devise mathematical models to describe systems. When you make a model, you must create stability in the model and ensure the process controller is stable. Stability is key. The ‘government system’ in Khartoum says that Sudan is an Islamic, Arabic country; they’ve forced the Arabic language on the Sudanese people, yet 70 percent of Sudanese don’t speak proper Arabic and there are many religions practiced, not only Islam. So it’s not only these two parameters that define Sudan; there are other parameters that define us. You must include all the parameters, including Arabs and Islamics.”

Do you think science can solve Sudan’s political problems?

“Mathematics is the most credible tool to describe nature. I believe it can be used as a tool to come up with solutions for political problems. When you come to Sudan or Africa and want to start making definitions, start making a system, you must include all the parameters. This is a very basic factor. It’s essential that everyone be represented inside their own country and government.”

Is it not possible to have both stability as well as an Islamic government in Sudan?

“It’s an issue of identity. We define ourselves as Africans, they as Arabs. You cannot and should not force an identity upon anyone. Someone owns an identity, so if I want to join an identity, the people that own it should accept me. There must be willingness from both sides, but the group of people owning an identity has the authority to accept you or not. For example, I can only call myself Dutch if the Dutch accept me as such.”

What then is important for establishing peaceful coexistence?

“You don’t need to force people to learn your language, to join your religion; you shouldn’t force them to join your identity. You can let people be as they are and see the common things that you share, focus on those things, and join people on those grounds.”

You’ve lived in the Netherlands for five years. Do you see a future for yourself here?

“Holland is nice; it’s safe here. There are tremendous opportunities for a good education here. TU Delft’s known around the world. If I’m lucky I’ll work in the aerospace sector, but right now I’m focused on my studies. I’m looking forward to my internship in Zurich in July. Of course I’d like to work in Sudan in future, but I’ll cross that bridge when I get there.”

What is your identity?

“I see myself more as an African than as Sudanese. If other African countries are struggling in instability, I cannot live well in a stable Sudan. When I speak to other African students, we all agree that it’s important to look out for each other’s interests.”

Is there such a thing as an African identity?

“Yes. For example, even though there’s huge tragedy taking place in Darfur, the African Union’s helping to solve it. Sudanese and Ugandan troops will also soon be deployed to keep peace in Somalia. These are good examples of sharing resources between African nations. This is a great step towards real unification.”

What are some positive developments in Africa today?

“Corrupt governments, dictators, are slowly being forced out of the African Union, paving the way for democracy. The president of Togo was recently forced to step down because he wasn’t democratically elected, for example. This is a very positive development for all of Africa. Hopefully in future all Africans will realize that we share a lot of traditional values and customs.”

I left Kacgor’s home that day wondering what parameters define me, what my identity was and whether it was an identity that could be owned by people of different nationalities, religions, sexes, races…an identity that always seeks the common ground, no matter how big the differences. I liked to think so, and I hoped I wasn’t the only one.

Ayuel Kacgor (Photo: Hidde van der Lijn, BSc, Netherlands)

Comments are closed.