Electronic waste is growing fast. European directives aim to increase recycling, but devices are hard to recycle. Designers can change that, says Dr Farzaneh Fakhredin.

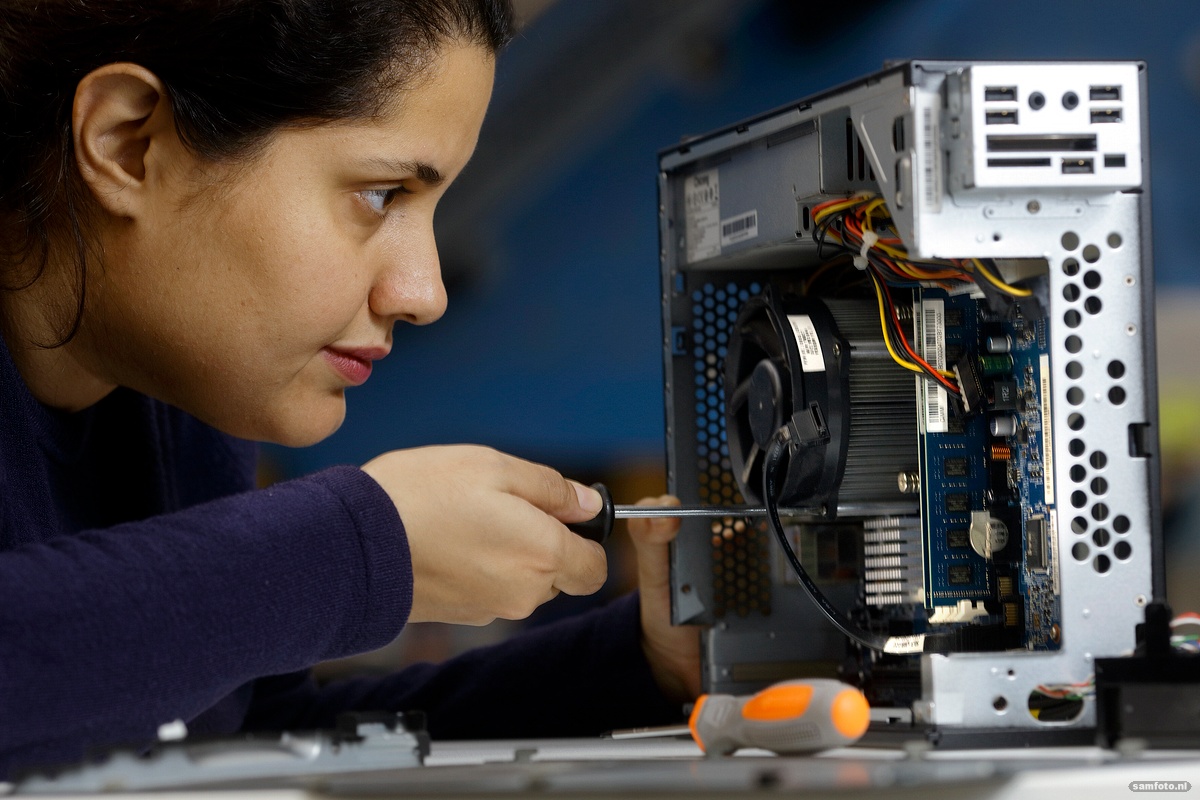

Farzaneh Fakhredin studied the disassembly of electronics (Photo: Sam Rentmeester)

Collecting stations are loaded with large heaps of discarded computers and electronics boards. In the next bunk: televisions, followed by washing machines and refrigerators. Waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) is one of the fastest growing waste streams in Europe with nine million tonnes in 2005, and expected to grow to over 12 million tonnes per year by 2020.

Photo: Sam Rentmeester

Photo: Sam Rentmeester

Go there and have a look, recommends Farzaneh Fakhredin. A recycling plant is an interesting place to visit for industrial designers. From their perspective, they can see that electric devices haven’t been made for recycling. “Think of a product’s end right at the beginning,” Dr Fakhredin argues. She did her PhD research on the gap between design methods and recycling practices at the Faculty of Industrial Design and Engineering.

“Think of a product’s end right at the beginning”

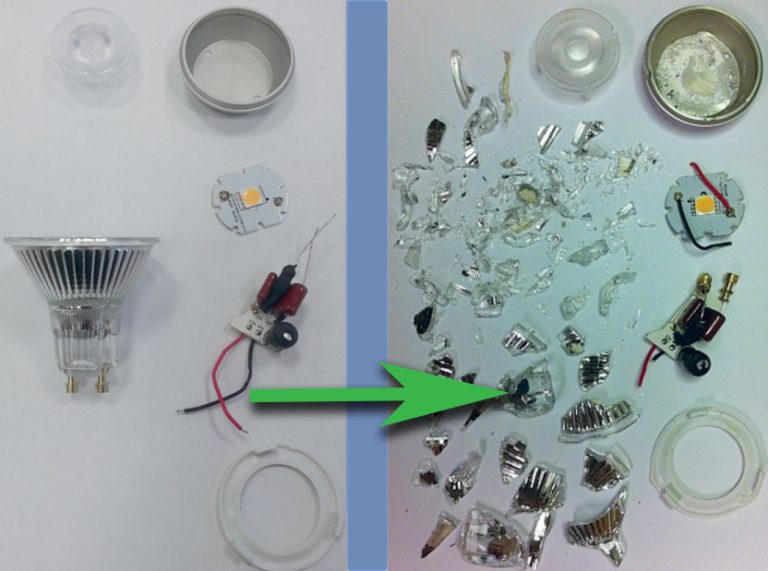

Dr Fakhredin didn’t shy away from hands-on experience in her PhD project. She disassembled medical displays and televisions, and she observed the result of shredding tests for LED lamps to see if materials could be easily separated for recycling. She studied which product design features hamper or facilitate the recycling proces. Salvaging electronic boards from displays for example takes up to 10 minutes. A large number of screws of various types, glued connections, and hard to reach connectors all make the process lengthy. In the case of LED lamps, the housing and electronic boards could not be well disintegrated mainly because of the glue and screw connections

redesigned LED lamp disintegrates neatly in parts

redesigned LED lamp disintegrates neatly in partsDisplays and LED lamps showed much better disintegration results when re-designed with circularity in mind. The dismantling time for LED LCD televisions, for example, was brought back from 250 seconds to 90 seconds, just by changing the design. Improved design LED lamps resulted in optimal separation of glass, metal, electronics, and plastics in the shredder.

Fakhredin argues that the focus on the European WEEE Directive is erroneous. It mainly focuses on maximising the amount of electronic waste collected from households. But as long as the collected electronic waste is not suitable for recycling, there will be very little progress in recovering raw materials, or increasing recovery rate for that matter.

It’s not only the collected amount that counts, but also the design of products that should enable the recovery of raw materials. The good news is that designers can improve product design for recycling, as Fakhredin demonstrated by having displays and LED lights redesigned for recycling.

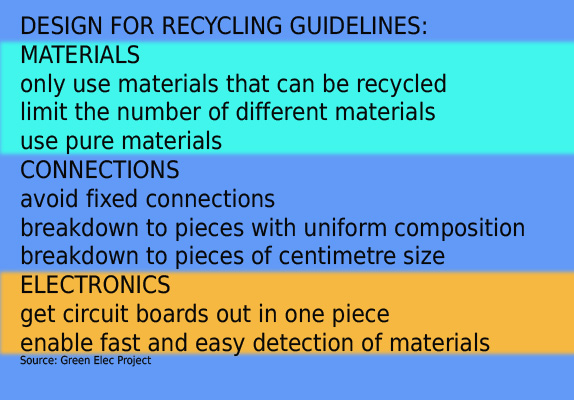

She says that design for recycling and circular product design should become a standard part of the design brief, yet it seldom is. Once designers think of a product’s end of life, they can design for improved recyclability. But they won’t do that unless their employer or client asks them to. Once the focus is on enhancing products recyclability, there is a host of guidelines available for designers (see below). Fakhredin sees a role for herself in improving circular product design by educating designers in industry and academia.

- Farzaneh Fakhredin, Design for Recycling of Electronic Products: How to bridge the gap between design methods and recycling practices, PhD supervisors Prof. Conny Bakker, Prof. Ruud Balkenende and Prof. Jo Geraedts at IDE Faculty TU Delft, 18 December 2018.

Do you have a question or comment about this article?

j.w.wassink@tudelft.nl

Comments are closed.