During his PhD research, anthropologist Leeke Reinders lived among the inhabitants of a post-war neighbourhood. He noticed that the end-users are often absent from the design process.

Dynamic neighbourhoods appeal to Reinders. For example, he lived for six months in the Paris banlieues, best known for the numerous cars that were set alight during the civil unrest in 2005. He found out that by saying bonjour, the youngsters distrusted him even more. Only when he learned a bit of argot (a slang term) and dressed a little wilder, he was allowed a bit nearer.

He used the same blending-in technique nearer to home, in the Schiedam district of Nieuwland. It’s a neighbourhood that was built according to modernist principles and offered working-class housing in four-storey flats with large communal lawns in between. Meanwhile lots of immigrants have moved into Nieuwland, resulting in tensions between old and new inhabitants. Renovations have been undertaken with the purpose of upgrading the area to attract young working families and make the housing more profitable.

Reinders wanted to compare the view of designers and policymakers with those of the inhabitants. Or, as he phrases it, he wished to study the hard city and the soft city; the city of stone and the city of the people who inhabit it. He noticed around him, and also when teaching students of Architecture (at the university of KU Leuven), that architects are less interested in the user’s perspective as the scale of their designs grows. City planners for example will as a rule not consult future inhabitants. But interior designers generally will. Perhaps not so much driven by personal curiosity as by the need of maintaining good customer relationships. An architect designing a house will tend to be more interested in the user when he/she also happens to commission the house.

The city planners’ perspective is usually well preserved in plans, maps, reports and designs. Reinders writes that Nieuwland, built between 1948 and 1965, follows the pragmatic version of the modernist idea based on the open neighbourhood. The strips of buildings with lots of open space in between designed to accommodate different social classes. Bringing the different classes together was to create a sense of community that would form the bedrock of democracy. Happy naive days indeed.

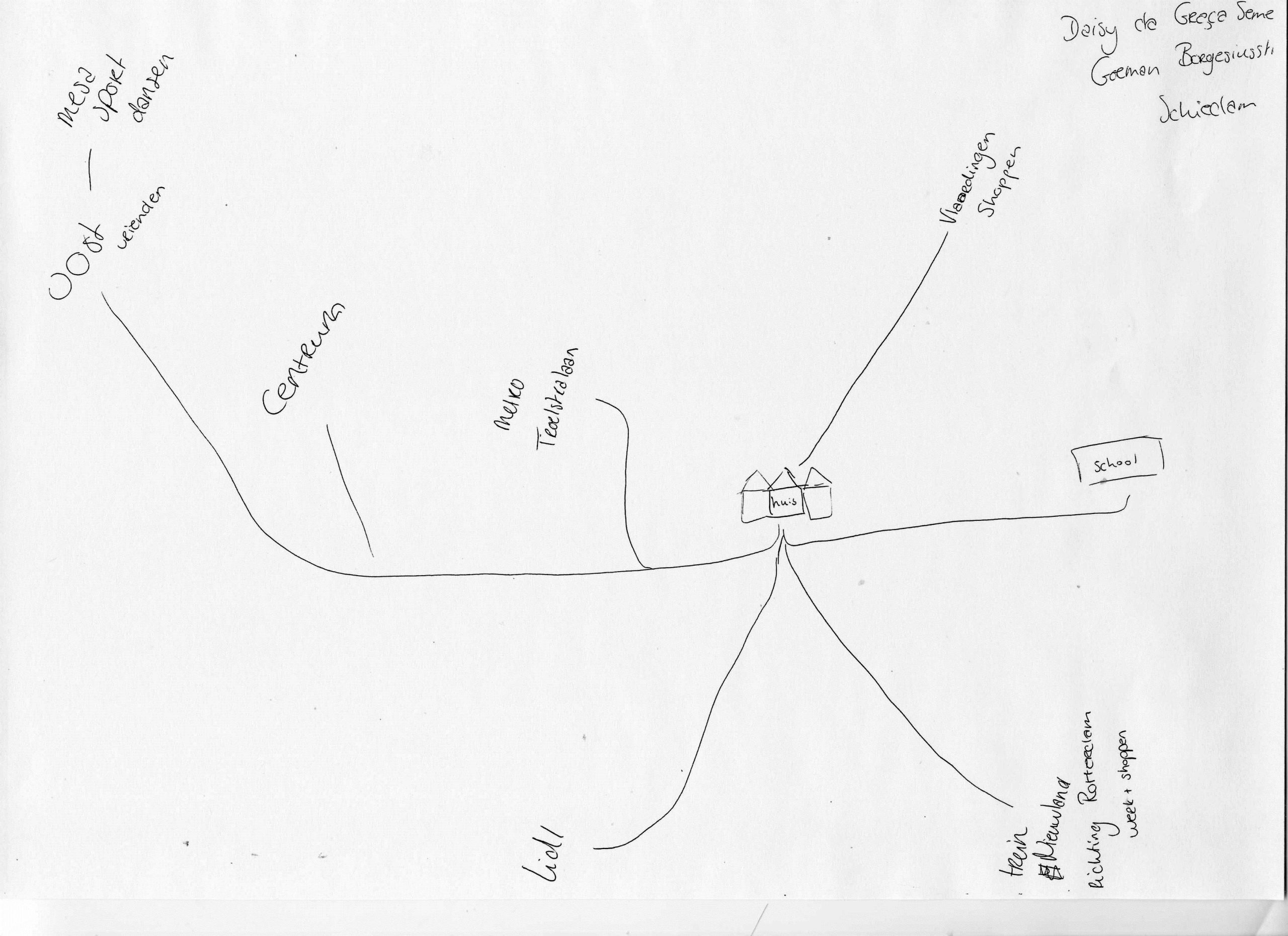

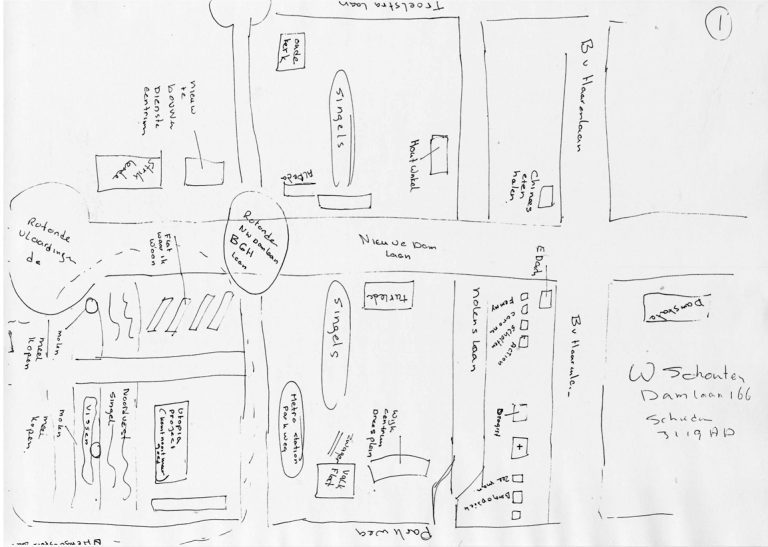

Reinders contrasts that view with those from the inhabitants half a century later. He used the technique called narrative mapping by having people draw their personal map while being interviewed about their surroundings. The outcomes are staggeringly various, and give unexpected insights in how people actually live.

There’s this basic outline by a 16 year-old girl who just has lived there for three months. Her world stretches out to the city centres of Rotterdam and Schiedam, but the map is mostly blank. There is much left to be discovered.

Another nice example is the map drawn by Achmed, a man of Turkish origin and a moderate muslim. His map features the (orthodox) mosque prominently, as well as the 3D sketches of the building blocks and some windmills along the river Schie. Achmed has looked well at the buildings, but they are loosely located.

And then there is Guus – a Dutch inhabitant who has lived there for a long time as you can tell from the details from his account:

“Here is the painting shop that was mentioned. It’s called Van Loenen and I visit it from time to time. These are the mills where you can buy flour. This is the subway station Parkweg and here the Troelstra avenue. These are the girths. When I walk there at night, I avoid people’s gaze. Because there are so many Turques there, I hardly dare to come around anymore. This is the service centre. And here is the high rise where my brother in law lives. And here is Damstaete (retirement home) across from the police station. My parents in law lived there, but now they have moved here. Next to the cemetery.”

Confronted with those radically different perspectives, Reinders recommends his Architecture students to go and visit a place before they start designing. “Look around, talk with some people, see how public and private spaces work instead of just starting up Google maps.”

Reinders also pleads for designing places with the users in mind, as the famous Dutch architects Aldo van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger (used to) do. They left room in their designs for people to find their own uses for spaces and forms. They created spaces where people could meet or seek seclusion. Reinders gets weary when he sees playgrounds that leave no room for play and imagination.

And, he knows it sounds like blasphemy, we should acknowledge that people like to live among peers. The segregated city may be taboo, but it is what people say they would like best, the anthropologist observes.

Leeke Reinders, Harde stad, zachte stad – Moderne architectuur en de antropologie van een naoorlogse wijk, PhD supervisor Prof. Peter Boelhouwer (OTB, Architecture), December 4, 2013.

Comments are closed.